The Knitting Machine

Replicating the colonial project in behaviour change.

When my mum and aunts bought a knitting machine in the 1970s, they weren’t just buying a gadget; they were buying the myth of progress. Acrylic yarns, bright, soft, and easy to wash, replaced wool. This promise of consumption as freedom (buy, make, upgrade, improve) still shapes our lives. But as the 2025 Waste and Resource Efficiency Behavioural Trend Report reveals, we are now counting the staggering, toxic debris of that very myth.

The report opens with hopeful optimism:

· 97% of respondents say they recycle.

· 95% say they try to reduce waste.

· 77% say reducing food waste is important.

All these behaviours, measured as individual effort, rinsing jars, using reusable bags, checking labels, and the structural conditions that create waste, remain untouched.

Three years of tracking found that low-commitment individuals remain static and resistant to change, and that high-commitment individuals (the “good recyclers”) are already doing all they can. Confidence in recycling has improved slightly, but trust in the system remains low, and confusion persists about what can even be recycled.

This is presumably colonial psychology rendered in data: the individual is counted; the system is not. The illusion of behaviour change functions precisely to distract us from the forces that create the waste.

Counting individual acts of recycling and restraint is not collective action, it’s colonial accounting. We are measuring obedience, not transformation.

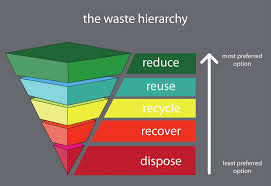

In the survey, most respondents “always” bring reusable bags (81%), recycle at home (68%), and carry reusable bottles (63%). Far fewer engage in practices like hiring, sharing, or repairing; only 14% borrow tools, and just 10% refill containers. These habits reflect a growing commitment to the waste hierarchy, yet they also highlight a narrow band of behavioural compliance. Frugality, once a common ethic of care and restraint, appears less visible, even though it offers a powerful way to reduce consumption upstream.

While these actions are commendable, they tend to be measured as individual virtues rather than collective leverage. When waste is framed primarily through personal responsibility, each behaviour becomes both a data point and a moral gesture. This framing can affirm our intentions, but it may also obscure the deeper work of challenging the systems that generate waste in the first place. Rather than choosing between feeling virtuous or powerful, we might ask how everyday actions, especially those rooted in frugality and repair, can reconnect us with systemic change.

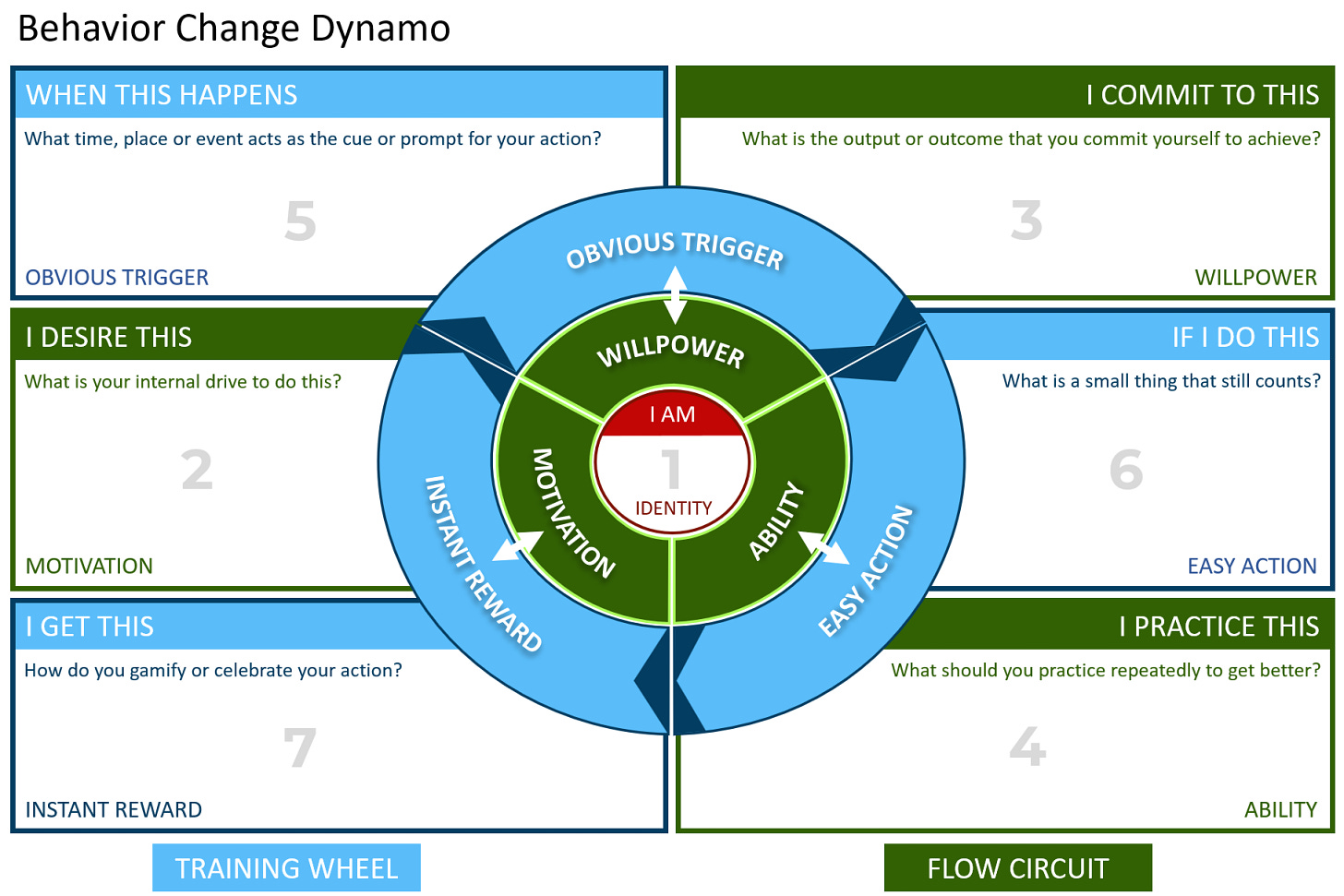

But how do citizens come to internalise waste management as an act of personal virtue?

The answer, I think, lies in the constant, subtle influence of modern marketing as the Soft Face of Control

In their analysis of “whitened fascisms”, the capitalist, nationalist, and moral regimes that normalise domination through everyday culture, the authors of Whiteness and Education (2025) identify modern marketing as a powerful tool. It tells us that to be a “good person” is to correctly sort waste, purchase sustainably packaged goods, and perform care through consumption.

The same logic drives state campaigns like Love Food Hate Waste or Plastic Free July: public rituals of individual virtue that mask the ongoing expansion of petrochemical and agribusiness empires. It is this subtle authoritarianism that moderates modern life.

Fascism teaches obedience through fear. Marketing teaches compliance through desire. Both reduce justice to a checklist of personal behaviours.

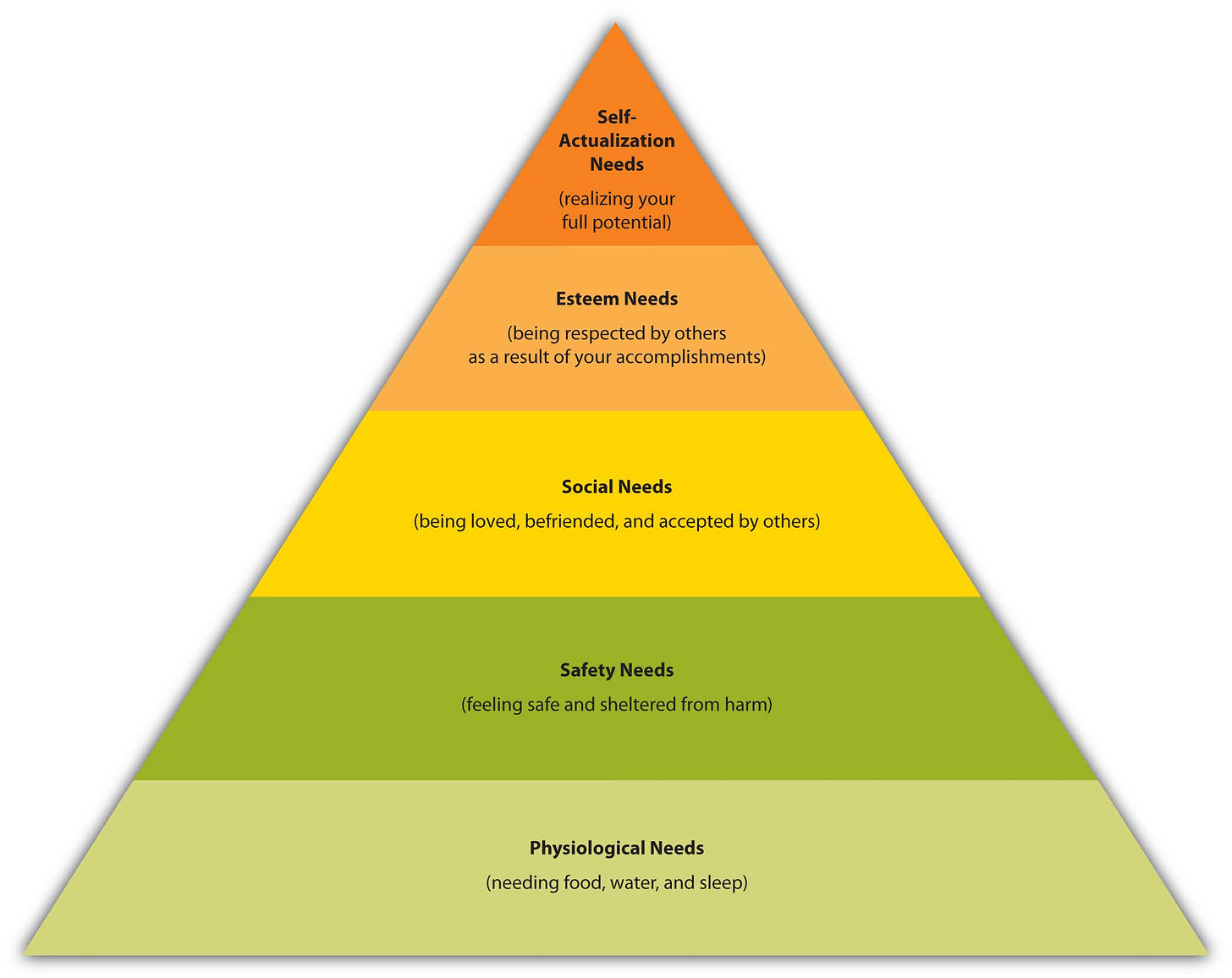

The Whiteness of “Good Citizens” is retold in the report’s segmentation of “high, medium, and low-commitment” recyclers reproduces a moral hierarchy eerily familiar to Aotearoa’s class and racial history.

High-commitment recyclers mirror Pākehā middle-class respectability, and their environmental virtue doubles as social status.

Low-commitment groups are pathologised, their structural barriers (rental housing, poverty, systemic neglect) recast as “attitude problems.

Māori and Pacific communities are statistically visible yet politically erased, treated as behaviour change targets rather than partners in systemic redesign.

These categories echo the colonial civilising project, where worth is measured by conformity to dominant norms of cleanliness, order, and restraint. The “good citizen” becomes the one who sorts properly and behaves responsibly, while the “bad citizen”, often poorer, busier, browner, becomes the site of intervention and education.

This is my understanding of waste colonialism as social science: a measurement of morality masquerading as a measurement of impact.

The report itself admits the cracks:

· Only 12% of people believe their individual efforts make no difference—a number that’s rising.

· One-third find recycling rules confusing.

· A quarter of households say they waste food because of busy lifestyles.

These are not failures of attitude; they are symptoms of a system that demands more of people while giving them less time, less control, and fewer collective options. People are tired. They are told that behavioural change is the path to salvation, but the landfill keeps growing.

The survey celebrates small shifts 6% more people moved into “high commitment”, yet national waste volumes, emissions, and extraction all continue to rise.

Counting actions without changing systems is the mathematics of managed decline.

Modern fascism doesn’t only march in uniform; it curates your feed. It defines “enoughness” through aesthetic virtue: the minimalist home, the clean pantry, the curated lifestyle that performs responsibility while depending on global exploitation. This is the new whiteness, tidy, anxious, moral. It sells the illusion that purity can be purchased and progress measured in self-discipline.

Our data dashboards mirror that same psychology. The Ministry’s graphs of 97% recyclers reassure us that order has been restored, that people are “doing their bit.” But systems built on extraction cannot be reformed through tidiness; they can only be transformed through redistribution of power.

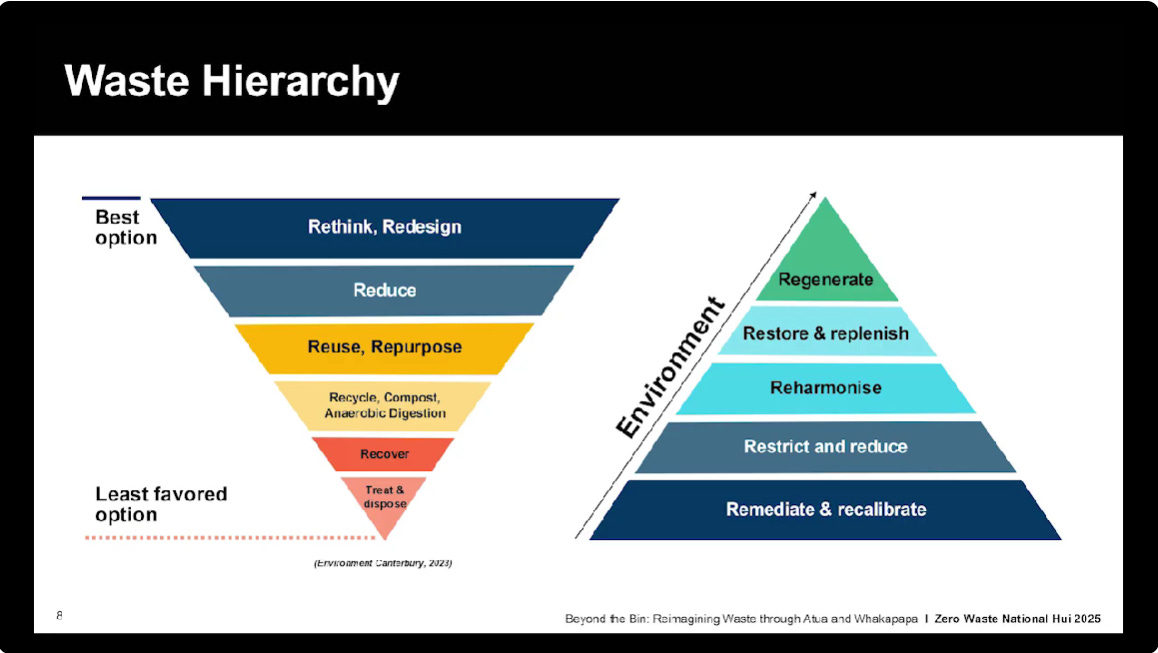

Kaupapa Māori worldviews challenge the very premise of this research. They remind us that behaviour is not individual but relational and that every action exists within connections that include shared responsibility to land and community.

If the report measured collective repair, shared governance, or mana motuhake over resources, its findings would look very different. Rather than segmenting citizens by compliance, it could show how communities are enabled to self-determine. It could reveal how resourcing local infrastructure and honouring Māori leadership in oranga taiao allows the Crown to begin fulfilling its Tiriti obligations.

Decolonisation reframes waste as a breach of the relationship with each other – tangata whenua, tangata Tiriti, tangata me ngā mea katoa o te āo tūroa.

The task before us is to build resistance to the waste economy, to the data economy, and to the fascism of measurement itself. We must create what Jupp et al. call communities of resistance and dissent where solidarity replaces surveillance, where learning replaces guilt, and where collective care replaces compliance.

Kaupapa Māori practice already shows us how: whanaungatanga as infrastructure, kaitiakitanga as governance, whakapapa as economy. Zero waste, in this frame, is a constitutional act. It is a rejection of supremacy and a reclamation of relationship.

If official reports measured time spent in hui, mutual aid, shared composting, or community repair, our data would tell a story of abundance. But as long as we count only isolated actions, we will mistake the performance of care for the practice of justice.

The opposite of waste is not recycling. It is rematriation—returning value, voice, and vitality to the systems capitalism stole.

True zero waste is constitutional work: a fundamental rebalancing of power, time, and purpose. My thanks and gratitude to L’Rey Renata for their work Beyond the Bin: Reimagining Waste through Atua, Whakapapa, and Interconnection and the lessons for resistance and liberation within this.

Further Reading:

Aotearoa Plastic Pollution Alliance - Te Rōpu Whakakore Para Kirihou