There Is No Away

A Personal Reckoning with Waste, Class, and Colonialism

Terry Pratchett introduced Sam Vimes's Theory of Socioeconomic Unfairness in his 1993 novel Men at Arms. It illustrates how poverty forces people to spend more money over time due to their inability to afford high-quality goods upfront.

In the book, Captain Sam Vimes explains that a good pair of boots costs $50 and lasts for years, while a cheaper pair costs $10 but wears out quickly, requiring frequent replacements. Over time, the person who can only afford cheap boots spends more than someone who could afford the higher-quality pair initially.

I grew up with leather shoes, and tins of nugget and dubbin, these were conveniently filled with sand and re-purposed for hopscotch when empty. I learned to polish my shoes regularly, and up until my teenage years, these served as school shoes, church shoes and good shoes. I had a fondness for T-bars, and to this day, I still have a thing for Mary Jane shoes. Alongside this, as is normal in rural areas, I had a pair of gumboots and a pair of jandals. In the summer, I tended toward bare feet, much better than jandals for climbing up macrocapa to pick the sweet rambling wild grapes, lying on riverbanks, and keeping out of Mum's way with my siblings, otherwise known as chore avoidance by flying beneath the radar.

As I reflect on those customs, I understand this pragmatic approach to footwear was inherently working class; buy something that would last, was repairable, and look after it so that it could be passed on in good condition. We were in no end of trouble if we came home without our shoes, and even more trouble if they were not found. Hand-me-downs reflect broader class dynamics, particularly in how economic constraints shape consumption patterns. Passing along clothing and goods is necessary for families and connected communities who want to maximise resources and reduce costs.

Our clothes were homemade, sewn, knitted, and shared. The cooler clothes of older cousins were a favourite because they were sometimes store-bought and resembled the clothes we saw on TV. “Happy Days” shaped my perceptions of cool in the early seventies. I remember a denim jumpsuit I adored as a hand-me-down because in my reality, it was ‘ABBA chic’. Fifty years later, it’s easy to romanticise these seemingly simpler times. But that would be overlooking the destructive impacts of neoliberal policy, the globalisation of markets and trade deals

The stigma surrounding hand-me-downs is real. As a single mum with three small and fast-growing children, I resented the necessity of second-hand shopping and the plethora of stained children's clothes with twisted and frayed seams. Children's clothes were often $2 a bag or grab a bag, and we quickly learned that all we were doing was saving the charities from a trip to the landfill. Somewhere between the seventies and the nineties, as a society, we changed from a culture of enough, an inbuilt resilience and resourcefulness, to an interdependence on capitalism and consumerism, swallowing notions of success and hard work not as identity and place but as dreams of freedom, beauty and buying power.

We are the product of class struggle and the social mobility promised by white colonialism and neo-liberal policy. Ultimately, hand-me-downs illustrate how class influences access to resources, consumer habits, and social perceptions, shaping economic survival strategies and cultural narratives around wealth and consumption. The colonial roots of capitalism reinforced these dynamics by commodifying goods, labour, and land, shaping modern consumption patterns that prioritise newness over necessity.

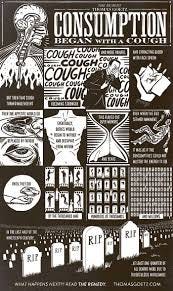

I often reflect on the expression “sounds like you’re dying of consumption”, a colloquialism for a bad cough.

And here in the now:

In Aotearoa, the working poor bear the weight of our throwaway economy.

At the community recovery centre, it’s every day people on low wages sorting through kettles that broke too soon and toys discarded before they were held. It’s the volunteer—maybe retired, on a benefit - mending jeans in the corner of a repair café, their fingers carrying skills from when things were made to last, not made to fail.

In charity op shops, it's underpaid staff and volunteers; overwhelmingly women, steaming fast fashion castoffs that will be landfill within a fortnight, dressed up as charity but built on the false economy of overconsumption.

These same workers, in community-led resource recovery enterprises, are rent-burdened by landlords profiting from housing scarcity. They wait months, even years, on the public health system’s backlogged lists, while their homes grow colder, and their food bills stretch thinner. And yet they keep showing up, patching what’s broken, caring for what others abandon, and keeping the repair ethic alive in a society obsessed with replacement.

Nature has always known cycles.

We were the ones who forgot.

But the wisdom is still there

in the mycelium, in the wetland, in the whisper of compost and time.

We don’t need to innovate our way out of collapse.

We just need to remember how to live within limits.

In truth, the circular economy already exists and is held up by those with the least, while those with the most still live in linear luxury.

Beyond our shores, it’s the children in Agbogbloshie, Ghana, pulling copper from the carcasses of our electronics. The children in Bangladesh are dyeing fabric in rivers that no longer run clear. The families in Indonesia are burning imported plastic waste to cook their meals, their skies heavy with toxins.

And it happens here, too. Our backyards are not immune. From the Pacific Islands saturated with New Zealand’s plastic exports to rural Māori communities disproportionately burdened with landfill proximity, the pattern is the same: extraction at one end, disposal at the other and profit in between.

Waste isn’t just what we throw away—it’s who carries the burden of our excess.

That $10 garment is stitched into a global pattern of extraction: cotton grown with fossil-fuel fertilisers in India, spun with chemical softeners in China, dyed in toxic vats in Bangladesh, shipped across oceans in plastic, worn once, then dumped in a bin marked “donations.”

This cycle reflects waste colonialism, where wealthy nations export plastic, e-waste, and hazardous materials to poorer countries lacking safe disposal infrastructure. These shipments, often disguised as “recycling,” end up burned, buried, or polluting waterways, harming communities already stretched thin.

Aotearoa is deeply entangled in this system, exporting low-grade waste while importing goods wrapped in polymers and relying on high-impact imports like crude oil, phosphate rock, and palm oil. We outsource environmental harm while distancing ourselves from its consequences.

Meanwhile, fossil fuel giants aren’t retreating; they’re rebranding. As the gasoline era wanes, oil is reborn as virgin plastic and chemicals. Polyester, nylon, acrylic, these synthetic fibres are fossil fuels disguised as convenience. By 2040, virgin plastic production is projected to rise 66%, not by accident but by design, sustaining fossil profits while sidestepping climate accountability.

Microplastics now permeate oceans, food, and human bodies; nanoplastics embed in lungs and organs, contributing to endocrine disruption, fertility decline, early puberty, and rising cancer rates among young people. These impacts fall hardest on working-class and marginalised communities, who face environmental hazards without access to adequate healthcare.

Wealthier populations can filter their water and buy private care, while others live with toxic exposure and limited treatment, deepening cycles of health inequity. And still, we keep buying. Algorithms and advertising train us to equate worth with appearance, success with style, and love with likes. For those with less, a new shirt or phone can feel like stylish success just for a moment, but it’s a poisoned gift, wrapped in wage oppression and environmental debt that lands on someone else’s doorstep.

Nature doesn’t produce waste.

There are no bins in the forest. No packaging on the wind. No landfill in the sea. Well, not until we put it there. Everything in the natural world is part of a loop. The leaf falls, the soil absorbs, the fungi feast, the insects carry and process, and the tree feeds again.

Waste is a design flaw of the growth and extraction economy. My resistance to the plastics industry is not just about rubbish. It’s an extension of my resistance to big oil, to colonising and recolonising the whenua, to all systems that oppress healthy environments supported by thriving communities.

I resist because both industries feed on the same colonial logic, the same patriarchal structures that strip land, steal labour, and silence communities. They take without consent. They exploit without accountability. They treat the whenua, the moana, and our bodies as disposable.

Landfills are the graveyards of justice built on stolen land. We tell ourselves we recycle. That we’re doing our part. But let’s be honest: recycling is the fig leaf of a linear system that was never intended to stop extracting. Only 2% of New Zealand’s material inputs come from recycled sources. The rest is ripped from earth, air and labour.

And while we invest millions in machinery to sort our shame, we leave the real solutions underfunded, the community repair hubs, the community-owned and led resource recovery centres, the zero waste educators, the kaitiaki working in harmony with whenua. These are the places where circularity lives.

The solutions aren’t new. They are remembered.

But we need to get past scientifically documenting and commentating our own demise. There is a bulk of information, stretching back at least a decade now, that affirms and reaffirms that there is too much plastic in the ocean, and that this is not a good thing. Plastic pollution denial at this point can only sit alongside climate change denial as intellectual self-harm. (Tina Ngata, 2018).

Further reading:

https://www.genevaenvironmentnetwork.org/resources/updates/plastic-production-and-industry/

https://www.barrons.com/articles/shell-chevron-oil-chemicals-plastics-d75f8fee?

https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/12/20/plastics-treaty-busan-negotiations-fossil-fuels-oil/

https://zerowaste.co.nz/

https://parakore.maori.nz/